During rain storms in developed neighborhoods, roofs, roads, and driveways direct water downhill, creating the torrents of water we see on the sides of streets. The rushing water picks up pollutants – metals from cars, roads, and rooftops; pesticides and fertilizers; road salt; and general sediment – and is channeled into the closest stream, untreated. The stream downhill from Holland Ave. is a Cobbs Creek tributary which means it ends up in the Delaware River, a prominent drinking water source. Cobbs Creek also contributes to major floods in downstream neighborhoods like Darby, Yeadon, and Eastwick. The first step towards restoring streams and reducing flooding is to improve conditions in small upstream tributaries.

As an organization devoted to protecting our waterways, the Conservancy is always looking for ways to reduce stormwater runoff. Many gutter downspouts and sump pumps on residential properties are piped directly to the street or the storm sewer. We find that many of these setups can be altered so that rain water is instead directed onto a garden or onto a lawn, benefiting the neighborhood without creating new problems.

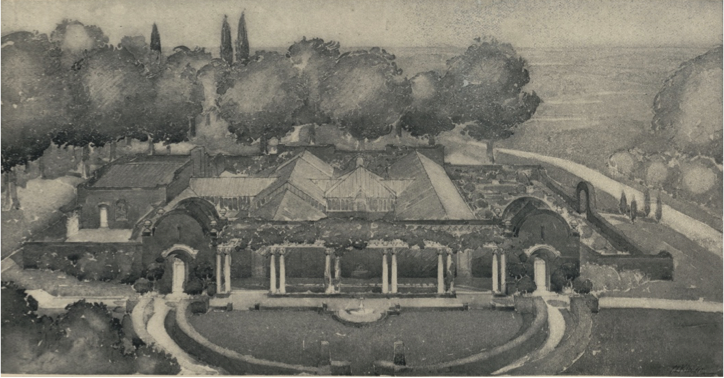

The Holland Ave. Area Green Street outlined.

In 2017, the Conservancy and a few of our partner organizations received funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to conduct “Stream Smart House Calls” where we visited individual properties to give recommendations for handling stormwater issues. Through Stream Smart we connected with a few interested residents on Delmont Ave. in Ardmore and we applied for a grant (also from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation) to let us install the stormwater recommendations and create our first Green Street. After the initial success on Delmont we applied for and received a larger grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection to expand the Green Street work. Being a tight-knit neighborhood with close proximity to a headwater tributary, we feel that Holland Ave. and the surrounding streets are a perfect Green Street area.

The approach on each property will fit into one or more of the general categories listed below. To get started, we can schedule a time to walk around your property. After the visit we will provide a list of recommendations and we can move forward with as many or as few as you would like. We always use native plants – plants indigenous to the Greater Philadelphia Area – because they attract birds, butterflies, and other beneficial wildlife.

If you are interested in participating or have any questions about the Green Street program, email [email protected] or call 610-660-2810.

Rain Gardens

Rain gardens are bowl shaped gardens designed to take on water from nearby rooftops, sidewalks, or driveways. During storms, water pools in the garden and slowly absorbs into roots or percolates into the ground. The process of trickling through soil cleans the water and prevents it from picking up more pollutants on the way to the stream. Rain gardens are our most effective tool for reducing residential runoff.

Garden Expansions

Lawns, bare soil, and unplanted mulch beds contribute to runoff and flooding because they do not absorb water as well as spaces populated with deeper-rooted plants. These have been our most common Green Street projects so far. Whether creating new garden beds, planting more densely within existing garden beds, or planting shrubs and trees within lawns, adding more plants improves water absorption and increases the ecological value of any space.

Depaving

Since paved surfaces are one of the main sources of our water issues, removing portions of sidewalks, driveways, or patios is a straightforward way to reduce runoff. To depave we break up and pull out the paved surface, fill the space in with soil, and create new gardens. Depaving projects do not have to be large, removing unused perimeter portions of sidewalks or driveways does make a difference.

Downspout Planters

Downspout planters are small metal troughs designed to filter and slowly release roof water. The upper half of the troughs are filled with soil and planted while the lower half is set up as a false bottom to hold more water. They are useful for downspouts piped onto driveways that cannot be re-routed onto a garden or a lawn.